- Home

- Shorty Rossi

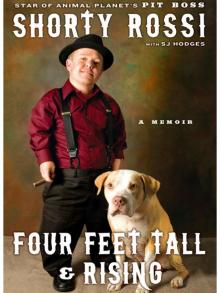

Four Feet Tall and Rising

Four Feet Tall and Rising Read online

Copyright © 2012 by Shorty Rossi

All rights reserved.

All photos are from the Luigi Francis Shorty Rossi Collection unless otherwise credited.

Published in the United States by Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Crown Archetype with colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rossi, Shorty.

Four feet tall & rising : a memoir / by Shorty Rossi; with SJ Hodges.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Rossi, Shorty. 2. Television personalities—United States—Biography. 3. Theatrical agents—United States—Biography. 4. Dwarfs—United States—Biography. I. Hodges, S. J. II. Title.

PN1992.4.R595A3 2012

791.4502’8092—dc23 2011035495

eISBN: 978-0-307-98589-7

Jacket design by Laura Duffy

Jacket photography by Cigars International

v3.1

It’s impossible to dedicate this book to just one person. So many people have influenced my life. So, instead, I dedicate this book to my six pit bulls: Geisha, Mussolini, Bebi, Hercules, Domenico, and Valentino.

If it wasn’t for them, I would not be who I am today.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1 The Little Baby Born

2 White Blood

3 Felon

4 Cat Man

5 Folsom

6 Slumlord

7 The Chipmunk

Photo Insert

8 Pimpin’

9 Welcome Home

10 The Boss

Epilogue

Essential Shorty

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Prologue

’ve got a big mouth.

I came out of the womb wailing and I’ve pretty much been yelling ever since. Over the years, I’ve learned some choice words, and I use them with abandon. Swearing adds some flavor to the yelling. Swearing is like putting whipped cream with a cherry on top of all those regular words. You get more for your money. Swearing is an art.

So I swear and I yell. A lot. I’ve got opinions and I make them known.

And yeah, I’m not an idiot. I know my big mouth isn’t the first thing people notice about me. I’m short. Shorter than most but taller than some, and in a world where short ain’t shit, you gotta do something to make sure you don’t get swept underfoot. Hence my big mouth. It’s gotten me into trouble and it’s saved my ass, and while it may not be the first thing you notice about me, I guarantee it’ll be the thing you most remember.

It’s this mouth that leads people to believe I’ve got a Napoleon complex. Like I’m overcompensating for my perceived handicap. Napoleon complex, my ass. That bastard was five-six—what’d he have to complain about?

Plus, I got good reasons to yell.

I yell ’cause somewhere in a Los Angeles basement, there’s a pit bull with duct tape wrapped around her muzzle, being trained to kill while money changes hands. I yell ’cause on some news program in Denver, there’s a politician demonizing pit bulls to further his own career. I yell ’cause some punk in Tampa’s got his fifth box of pit puppies and I know they’ll end up in the last cage of an animal shelter before they’re two. I yell ’cause humans can be the most brutal and heartless animals on the planet. I yell ’cause a pit bull can’t and somebody needs to.

I yell ’cause pits are my family.

We are the same breed. We are short, muscular and stocky, misunderstood, and much maligned. We’ve got hard heads, short hair, and our “bad” reputations precede us every time. We are judged by the actions of a few. We are treated like the enemy before we even make your acquaintance. We are feared. We are banned. We are excommunicated.

Pit bulls and ex-cons, we got a lot in common.

Except, I don’t wear my heart on my sleeve, and I’ve got no patience for stupidity. I can’t sleep all day and I much prefer a good cigar and red wine to a bowl of mashed beef. I might stand at crotch level but I’m not gonna sniff you. And trust me, if you raise your hand to me, I won’t be the one ducking and cowering.

On second thought, I guess, in most ways I’m not like a pit at all.

They’re much, much nicer than me.

1

The Little Baby Born

was ripped from my mommy’s womb on the 10th of February, 1969, in a doctor’s office in West Covina, California. My mom is a Little Person, and Little moms just aren’t big enough for a baby’s head to be delivered naturally, so like the three kids born before me, I came by C-section.

First in the lineup was my sister Linda, born in 1960. She was what Little People call tall, what others might consider to be of average height, and from the nuts of a different daddy, a fact I discovered much later when I was in prison and started researching my genealogy, digging into my family’s past to try to understand how I ended up behind bars and why I was the way I was. I found a birth certificate and a marriage license that proved Linda was born two years before my parents even met and married. It wasn’t the only secret I unearthed. There were lots and lots of secrets.

Another of those secrets was Michael, a baby boy born less than two years after Linda. Michael’s baby picture hung on the wall of our living room, a constant reminder that Dad’s first son had died young, barely two months old, of pneumonia. But the truth was Michael didn’t die of pneumonia. Michael died of double-dominant syndrome. Michael inherited two “bad genes,” two dominant achondroplasia (dwarfism) genes—one from Mom and one from Dad. Usually a baby that is double dominant doesn’t even make it to delivery. The mom miscarries or there’s a stillbirth. But Michael somehow beat the odds and made it to the world just in time to leave it again.

So Mom and Dad got back in the bedroom and tried again, and on December 18, 1963, my sister Janet was born. Like my sister Linda, Janet was born tall. The chances were fifty-fifty that the babies would come out “normal.” Mom and Dad rolled the dice three times and won twice. They were so proud. Two tall daughters. Success.

Why they waited another six years, until 1969, before they had me, I don’t know. They were Catholic but that didn’t mean Mom wanted a big family. Babies are usually hard on Little women. Most of them have at most one or two kids ’cause they suffer from so many miscarriages and problems. But I guess Dad always wanted a boy. Having lost Michael, and with the odds in his favor, he decided to roll the dice one more time. Plus, Mom had handled her other pregnancies without much trouble, so it seemed like everything would work out again.

I was the heaviest baby of all. Eight pounds plus. They knew the minute I came out that I had achondroplasia. It’s easy to tell, trust me. You know if you have a dwarf child. Back then, there was no way to predict such a birth. Now, doctors can diagnose dwarfism in the womb, giving parents the option to terminate pregnancies. They can even spot the chromosome that indicates double dominance. Now, even dwarf parents, who would be least likely to care if their child is Little, can still choose to terminate a double-dominant pregnancy. There will be fewer and fewer of us walking this Earth. There already are.

I was a third-generation Little Person, the son of dwarf parents and the grandson of a maternal dwarf grandma. Being third generation, my diagnosis was dismal. The more a dwarf reproduces, meaning the same dwarf, the weaker the genes, the more chances to trigger a double-dominant gene. The doctors told Mom and Dad I wouldn’t live long, and even if I did, they predicted I’d have severe physical limitations, suffer from limb deformities

, and be in constant pain. They basically pronounced me handicapped, useless, and dead. They were wrong.

This is why other Little People are shocked when they find out I’m third generation. I should be dead or deformed, and I’m not. I was so physically fit when I was a kid—young and active—it actually caused resentment. Some first-generation dwarves are all fucked up physically. They’ve got back problems and leg problems. They walk with braces, crutches, canes, or are stuck in wheelchairs. I was supposed to die young. I didn’t. I am a rarity.

Looking back, I wonder if my birth was the moment when Dad gave up on me. He’d grown up the only Little Person in a family full of tall people and he was ashamed of his size. He suffered from a bad case of self-loathing. He saw himself in me; his troubled legacy continuing against his will. Of course, that was never said to me. God forbid the truth be told. No, instead I was told that Dad was happy as hell when I was born. He’d always wanted a boy. He just didn’t know he was gonna get this wonderful specimen.

His entire family descended from a brood of big, bad revolutionaries based in San Antonio, Texas. His great cousin, by marriage, was Jim Bowie, defender of the Alamo, and his grandmother was Anna Navarro, a woman considered to be a serious agitator in the Texas revolution. The Navarros were from Corsica originally, Italians, with some Spanish blood mixed in. The Rossis were also Italian, but northern Italian, with a last name referring to the plural form of the Italian word for “red.” They named my dad Melvyn Louis Rossi. He hated his name. He went by Sonny instead.

There was no history of dwarfism in their family tree, so when Dad was born the son of two tall parents and the sibling of four tall sisters, he was considered a genetic malfunction. He had a broad, high forehead, a pointy chin, and prominent ears. In profile, his dwarf features were even more noticeable. He had a face as concave as a waxing moon. Dad had a typical dwarf nose, upturned and somewhat hooked at the same time. His hands had a kind of built-in V between the third and fourth fingers. It was not something easily seen, but his plump, short fingers didn’t quite close together. They had to be forced. His legs were slightly bowed.

They’d never seen the likes of him before. Born in 1936 and growing up in Texas in the ’40s and ’50s, Dad faced the same kinds of problems that black folks were facing: blatant prejudice and discrimination. Much worse than anything I’d ever have to handle. And it wasn’t just that he battled it in the world. He came home to it every day. Though his mom, Elsie, was a practicing Catholic and Italian who raised her kids to believe in the importance of family, she couldn’t control the actions of her husband. My grandfather made my dad’s life a living hell. Which is why we were told he was dead; that he died before any of us kids were born. This turned out to be another one of Dad’s secrets. His dad wasn’t dead. He didn’t die until the 1990s, but Dad never spoke a word about the man.

My mom’s childhood was a bit easier. She was born in Los Angeles but ’cause her mother was Southern, she was given a Southern name: Dixie Lee Brown. My mom’s father, whose name was either Fred Stevens or Chester Brown—depending on which birth certificate he was using at the time—was over six feet tall. Her mom, my grandma, Mary Brown, or Nonnie, stood only three-foot-seven. They were a married couple working in the circus, though I’m not sure which company. By the time they had Mom, Nonnie and Fred/Chester had retired from circus life. Tragically, Fred/Chester died of tuberculosis nine years after Mom was born, around 1945. Mom only half remembered him. Nonnie never remarried.

Mom and Nonnie looked like each other, and for the most part, I looked like them, too. We all had round cheeks and chins, wavy, sandy-blond hair, the same smiles and the same pudgy, triangular noses. In a world where we were different, we could look at each other and see similarity. It was a great gift. One that Dad never experienced as a kid.

So, at seventeen, he left his family in Texas and moved to Los Angeles. L.A. was, and still is, more accepting of Little People than most of the world. It was the home city of Billy Barty, a well-known film actor who founded the organization Little People of America. There was always work in Hollywood for Little People. Back then you weren’t a doctor or a lawyer, you were a Munchkin. You wanted to be a Munchkin ’cause it paid well. You couldn’t get a job doing other things unless it was demeaning or hard labor, and none of them paid like Hollywood. So most Little People moved west with dreams of tap-dancing down the Yellow Brick Road.

Dad had no such intention. He’d always wanted to be a mechanic, but growing up, he had to hide his tools under his bed ’cause his dad would beat the crap out of him for wanting to work a real job. He just figured his son was a circus freak. That he shouldn’t have any hopes for anything other than a life of freakdom. Grandpa must have thought he could beat the mechanic out of Dad, but it didn’t work. Dad got his first job with Lockheed. He was hired as a riveter for airplanes ’cause he was able to fit into the small places. How he met Mom, I’ll never know. They never talked about their relationship or their past. The only thing I knew for certain about their marriage was that Mom was treated more like a slave.

Dad preferred a regimented life; we all had to work and live around his schedule. Dinner was always at five o’clock. No matter what. God forbid Mom was one minute late with his dinner, and if I dared to show up at 5:10 p.m., I wasn’t allowed to eat. There was no talking or laughter around the table. Dad would just inhale his food as if eating was a task to get done so he could go sit in front of the TV. There was no meaning or purpose or feeling behind anything he did.

Mom was not a modern-day, feminist woman. She woke up earlier than Dad, made sure his coffee was going, and packed his lunches. I can still see him coming home after work and sitting in the breakfast nook where Mom had his beer and his chips and his salsa ready and waiting. She’d take off his shoes and socks. She waited on him, hand and foot. Her reward? Verbal abuse. And though we never saw him hit her, me and my sisters, we all knew he beat on her. We could hear them fighting in their bedroom. We could see the results.

Verbally, he was just as abusive to my sisters but physically, no. They were fearful of him, even though they were twice his size. When it comes to control, size doesn’t matter. Intimidation is a powerful motivator. Two paddles hung on our kitchen wall, one with holes and one without. They were a constant reminder that violence could happen at any second.

Dad never had to hit my sisters, ’cause he was beating the shit out of me. I might have been the biggest baby born, but I was the smallest kid growing up. That never stopped Dad from whipping the shit out of me. The spankings started when I was a toddler and they were never hidden away. The minute I did something he didn’t like … a spanking. No questions even asked. Mom never tried to stop him. She wasn’t physically abusive herself. She was a “wait until your dad gets home” kind of mother. She let him do the dirty work.

This is why I spent as much time as I could with Nonnie. I was closer to her than anyone else in my family. She loved for me to visit and stay with her. She always made sure I was entertained. She played with me and sent me cards and letters. She taught me to speak Italian. No one else ever paid much positive attention to me. Everyone else was always screaming about what I’d done wrong. I always knew Nonnie loved me. She was a warm and generous person when no one else was. Nonnie was the most, if not the only, positive influence in my daily life.

When I was really young, Nonnie was a wee bit chubby. She was diagnosed with high blood pressure and her doctor put her on a diet that worked. She lost the weight and got healthier. Dad thought Mom was pudgy, so when they visited Nonnie, he announced, “You need to teach my wife your eating habits.” Right in front of everybody. Mom said nothing, but we all knew her feelings were hurt. Even as a tiny kid I understood that my dad was an asshole.

Around the time I turned four, Dad decided El Monte, California, where we lived, had become “too ethnic.” The neighborhood wasn’t the lily-white neighborhood it had once been, so Dad packed us up and moved us all to Reseda in the San Fernan

do Valley, another suburb of Los Angeles.

Now, Reseda saw its big population boom in the ’50s, when a house there would cost you less than ten grand. Until the civil rights movement in the ’60s, the home owners of Reseda kept the area white, white, white. They actually had laws on the books that excluded nonwhites from owning land and houses until the Federal Fair Housing Act passed in 1968. By the time we got there in ’73, not much had changed.

The houses in Reseda were all ranch style and every yard was surrounded by a six-foot brick wall. Dad was the type of person who wanted to be left entirely alone. He was the kind of guy that once he got to a friend’s birthday party he wanted to leave immediately. He was so antisocial he raised the wall surrounding our house by another four feet, so no one could see inside the yard. He put screens on the outside of the house so we couldn’t see in or out. He was convinced someone was gonna rob us. He lived a paranoid kind of existence, and we were all at his mercy. Trapped like prisoners in our own home.

In El Monte, Dad had been a drag racer. He spent his weekends at the speedway, racing those long-nosed, fast cars with the parachutes that pop out the back to keep them from crashing. Our backyard in El Monte had been filled with all kinds of car parts. When we moved to Reseda, the cars disappeared and were replaced by a machine shop in the garage. Dad’s garage was hallowed ground. We weren’t allowed in it. Not one step over the door frame.

In that garage, Dad built anything he wanted. He’d construct furniture, rebuild a carburetor, or tinker with an engine. He turned a two-wheel bike into a three-wheel bike and custom-built his own little motorcycle. If he’d wanted, he could have built a house from scratch, but Dad had no interest in customizing our house. Every Little Person learns to customize the things around them in order to live a more comfortable life, but Dad only improved those things that he himself used, like the dragsters. Despite his talents, he wouldn’t retrofit our house. Instead of tearing up the kitchen and lowering the counters, we had to use stools or stepladders. When I visited other Little People’s houses, they could stand on the floor and easily reach their tables, their cabinets, their couches, their TVs. My dad refused to make any changes. He could have easily worked around Linda and Janet’s needs and included them in whatever plans he made. But Dad never wanted to admit he was a Little Person and he wanted everything to look “normal”—outside and inside.

Four Feet Tall and Rising

Four Feet Tall and Rising